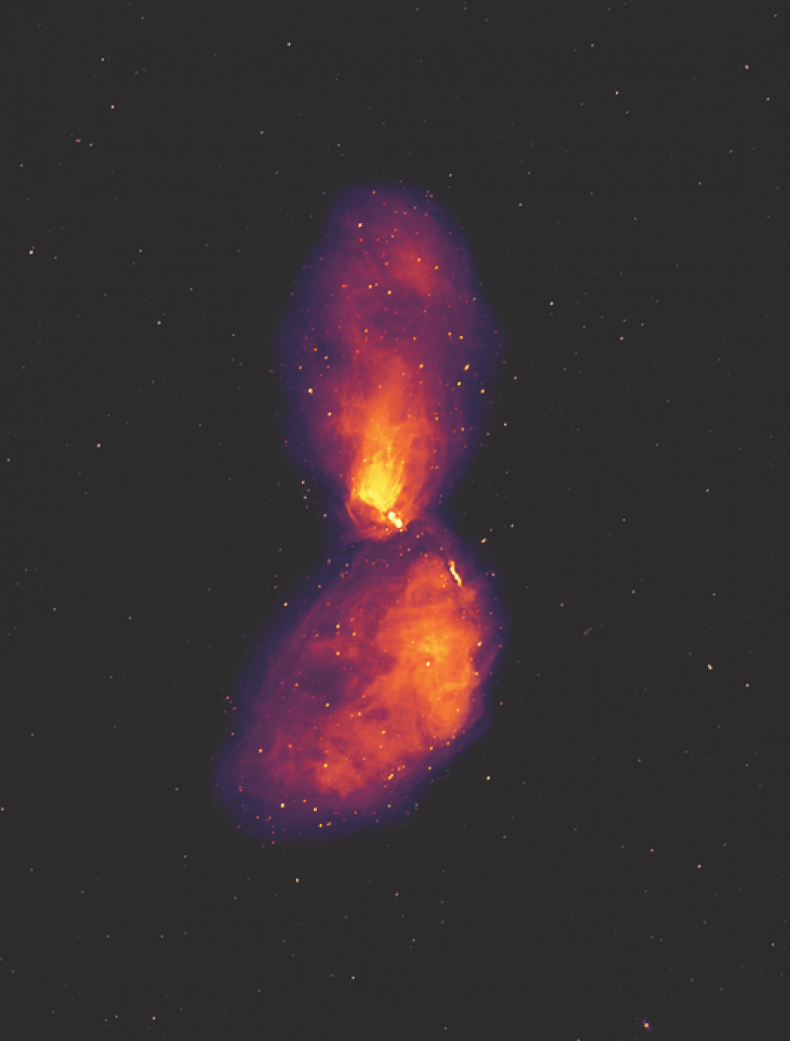

Astronomers have created the most detailed image ever of powerful radio emissions blasted out by the closest feeding supermassive black hole to Earth. The emission is fueled by the central supermassive black hole of Centaurus A, a galaxy located around 12 million light-years away.

The black hole at the heart of this galaxy, one of the largest and brightest objects in the night sky when viewed in radio waves, has a mass 55 million times that of the sun and is greedily consuming gas and matter that surrounds it.

The image produced by the team shows massive lobes of plasma stretching far beyond the limits of the galaxy. These are created as the black hole ejects material at near light speed.

This causes these "radio bubbles"—visible in the radio wave region of the electromagnetic spectrum—to grow over hundreds of millions of years.

Benjamin McKinley, from the Curtin University node of the International Centre for Radio Astronomy Research (ICRAR), said that these emissions could stretch over one million light-years into space.

"These radio waves come from the material being sucked into the supermassive black hole in the middle of the galaxy," McKinley, the lead author of a paper detailing the research set to be published in Nature Astronomy, said. "It forms a disc around the black hole, and as the matter gets ripped apart going close to the black hole, powerful jets form on either side of the disc, ejecting most of the material back out into space."

McKinley points out that in the image, it appears that Centaurus A is brighter towards its center where it is more active, and where there is more energy. He continued: "Then it's fainter as you go out because the energy's been lost and things have settled down."

Handling "Extreme" Radio Jets

McKinley adds that until now radio observations had not been adequate to capture these powerful jets. He said: "Previous radio observations could not handle the extreme brightness of the jets and details of the larger area surrounding the galaxy were distorted, but our new image overcomes these limitations."

McKinley and the team conducted their observations with the Murchison Widefield Array (MWA) telescope located in Western Australia. They combined these radio images with observations made in both optical and X-ray wavelengths.

MWA director Professor Steven Tingay said the research was possible because of the telescope's extremely wide field of view, superb radio-quiet location, and excellent sensitivity. He explained that the MWA telescope is the precursor to the Square Kilometre Array (SKA), part of an initiative that aims to build the world's largest radio telescopes in Western Australia and South Africa.

Astrophysicist Massimo Gaspari, from Italy's National Institute for Astrophysics, said that the findings arrived at by the team conform to a model in physics known as Chaotic Cold Accretion (CCA).

"In this model, clouds of cold gas condense in the galactic halo and rain down onto the central regions, feeding the supermassive black hole," he said. "Triggered by this rain, the black hole vigorously reacts by launching energy back via radio jets that inflate the spectacular lobes we see in the MWA image. "

Gaspari also points out this study is one of the first to probe the multiphase CCA 'weather' over the full range of scales in such detail.

McKinely concluded: "In this research we've been able to combine the radio observations with optical and x-ray data, to help us better understand the physics of these supermassive black holes.

"We can learn a lot from Centaurus A in particular, just because it is so close and we can see it in such detail."

Post a Comment