For the first time at trial, the Crown argued Martell is guilty of first-degree murder because he killed Ally Moosehunter during a sexual assault.

Warning: Graphic content

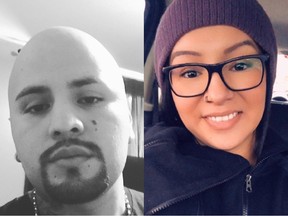

The Crown hasn’t proven that Ivan Roberto Martell is guilty of first-degree murder, or that he was involved at all in the killing of his off and on girlfriend, Ally Moosehunter, Martell’s lawyer told a Saskatoon King’s Bench courtroom.

Making his closing arguments at Martell’s judge-alone trial on Thursday, Patrick McDougall said first-degree murder requires planning, intent or confinement.

“There is absolutely no evidence that could be twisted in any direction that (Martell) committed first-degree murder,” he argued.

For the first time at trial, Crown prosecutor Linh Lê argued Martell is guilty of first-degree murder because he killed Moosehunter while sexually assaulting her. The Criminal Code of Canada classifies murders committed during sexual assaults as first-degree.

Lê said there was a sexual component to Moosehunter’s murder because her torn pants and underwear were pulled down and a knife handle was inserted in her rectum. It doesn’t matter whether the victim was alive or dead when it happened, she argued.

“Logically, the act of inserting the knife into her rectum followed the cutting of her pants and underwear. And at some point around the time of the cutting of her clothes, the stabbing, striking, and manual strangulation also occurred, all while she was alive,” Lê said.

“Therefore, the killing and the sexual assault are all part of the same continuous sequence of events, connected temporally and causally, making it a sexual killing.”

We may never know why Moosehunter was killed — which might not sit well with human curiosity — but the Crown is not required to prove a motive in order to prove guilt, Lê said.

Alibi and possible suspects

He said he woke up that afternoon, checked his phone and saw online posts saying he was wanted for Moosehunter’s murder. He could not say who made the posts, and never tried to call Moosehunter, her friends or her family, Lê said.

She noted the alibi evidence was disclosed for the first time at trial, making it virtually impossible to investigate more than three years later. She asked the court to “draw an adverse inference” due to the delay and “multitude of problems,” including having no contact information for the people he said he was with, and his cellphone records not putting him in the Riversdale neighbourhood where he said he had fallen asleep.

Although the couple was in a “rocky” relationship, breaking up and getting back together since 2015, there was no evidence of any prior domestic violence, McDougall argued.

He said the Crown is trying to establish that Martell was so jealous and distraught about his relationship with Moosehunter that he would kill her to keep her away from other men.

Martell said Moosehunter told him she was dating another man while he was incarcerated, but her sister testified they weren’t together.

McDougall noted that no other potential suspect was ever pursued.

“The Saskatoon Police Service was focused on one person and one person only, and that was a mistake in my opinion,” he said.

Court heard about text messages between Moosehunter and Martell the night she died, indicating that her door was unlocked and a key was left outside for Martell.

McDougall said it’s “plausible” that somebody else went into her home that night. Neighbours testified that a drug dealer used to live there, and Martell admits he was using and selling drugs at the time.

He posited that the person who killed Moosehunter could have been a spurned ex, or someone in the drug world Martell owed money.

Lê said the killing was by someone she knew well and trusted — someone who had access to her phone to text family members after she died. There were no signs of a break-in, and every valuable item in the home was left untouched, she noted.

Martell had bruises and cuts on his hands upon his arrest, consistent with an altercation, and a bruise on his hip, a police officer testified. Martell said he fell on some ice.

Timeline and DNA

He testified that he called his father on the afternoon of March 4, 2020. However, Lê said Martell’s cellphone made two outgoing calls to his brother and father just after 5 a.m. from cell towers in the Hampton Village neighbourhood.

Someone can be seen leaving the house around 9:10 a.m. and driving Moosehunter’s Jeep. The Jeep was later found in a parking lot on Pendygrasse Road. DNA from a blood droplet found on the door runner matched Moosehunter’s DNA, Lê said.

McDougall argued there’s no evidence that Martell was the person who left the home and drove the Jeep.

Lê said the accused never testified about either of those things happening.

A decision has been scheduled for May 19.

Post a Comment